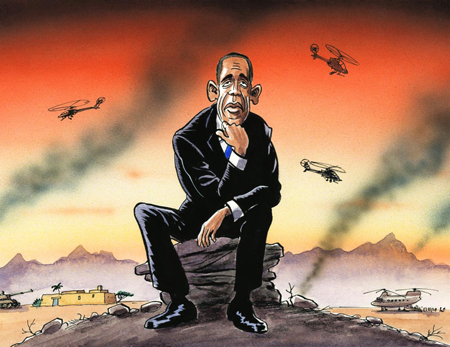

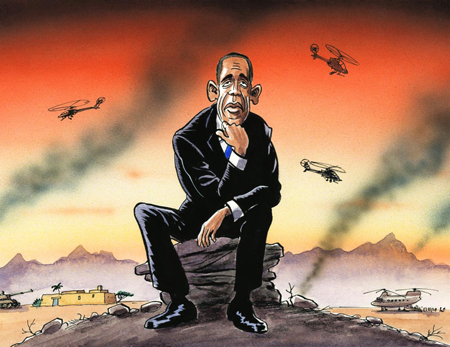

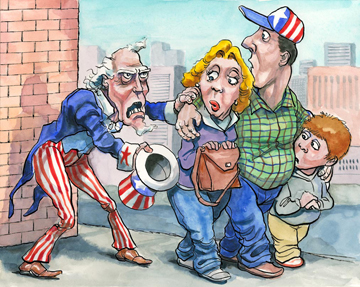

| Illustration by Peter Schrank |

The

president's rocky fortnight

Down in the valley

The man who can is

suddenly looking unsure of himself

|

|

|

|

BARACK OBAMA ran an impressively disciplined presidential campaign. He has presided over a notably cohesive White House. But in the past fortnight things have started to go wrong. His latest review of strategy in the Afghan war has prompted charges that this president dithers while American soldiers die, and has provoked a rare public quarrel between the politicians and the military men. The timetable for reforming health care slips and slips, as does the effort to get a climate-change bill through Congress. And in the middle of all this Mr Obama and his wife Michelle found time last week to make a quixotic overnight dash to Copenhagen in the hope of winning the 2016 Olympics for his adopted city of Chicago.

What was intended to be another display of star power on a world stage ended in a flop. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) eliminated Chicago in the first round, for some reason rating the delights of Rio over those of the Windy City. Tall and athletic he may be, but in Copenhagen America’s president won nothing and the Olympic gold went to the portlier president of Brazil, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

The Olympics, admittedly, are just games; the point, said the White House (afterwards), is that Mr Obama took the time to give Chicago’s bid his best shot. That has not stopped gleeful critics from depicting the failure as a symptom of bigger defects, notably Mr Obama’s overweening self-belief, and the naive trust they say he invests in unreliable foreigners, be they the bureaucrats of the IOC or the nuclear-arming ayatollahs of Iran. Rush Limbaugh, a conservative radio broadcaster, gloated that Mr Obama’s bad day in Copenhagen was the worst of his presidency, at least so far. “So much for improving America’s standing in the world, Barry O” sneered Erick Erickson, a blogger who runs the Red State website.

This debacle may not inflict lasting damage on Mr Obama. The delight some Republicans have shown in a setback for an American city could hurt them more than him. But the dash to Copenhagen was plainly under-prepared. It has bashed his reputation for a sure touch in public relations and added to the suspicion that he expects to achieve too much merely by deploying his celebrity power. Valerie Jarrett, a family friend from Chicago and one of the president’s very closest advisers in the White House, gushed before the Copenhagen trip that the Obamas would be a “dynamic duo” in Denmark. David Axelrod, another, complained afterwards of the IOC’s decision that there were “politics inside that room”. Isn’t the president of the United States supposed to know a thing or two about politics?

Nobody, however, can accuse Mr Obama of under-preparing for the far weightier decision he is pondering in Afghanistan. The administration has now spent several weeks conducting a methodical new review of its strategy, prompted by two deeply unwelcome developments: the crude rigging in favour of President Hamid Karzai in August’s flawed election and the leaked report from General Stanley McChrystal, concluding that the West faces certain defeat unless it adopts an ambitious new strategy, backed by a greater commitment of men (said to be 40,000, though the number has not yet been confirmed) and resources.

That General McChrystal’s report has divided the administration is no surprise: the war is now very unpopular among Democrats who have been encouraged by their success in imposing a rigid timetable for a full withdrawal from Iraq. The surprise is that it has prompted an unusually public quarrel. Vice-President Joe Biden rejects the call for an enlarged counter-insurgency campaign against the Taliban. His is said to be one of several voices inside the White House arguing for a smaller war directed mainly against al-Qaeda. But the merits of the case have now become ensnared in a debate about whether General McChrystal was insubordinate when he appeared to disparage the Biden idea in public. “You have to navigate from where you are, not where you wish to be,” the general told a questioner at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, a think-tank in London. “A strategy that does not leave Afghanistan in a stable position is probably a short-sighted strategy.”

The charge of insubordination sizzled rapidly through the media and up the chain of command. Writing in the Washington Post, Bruce Ackerman, a professor of law at Yale University, went so far as to invoke the spectre of Douglas MacArthur facing off against Harry Truman over the Korean war. He accused General McChrystal of “a plain violation of the principle of civilian control”. Jim Jones, the National Security Adviser (and a former general), said a president should be given a range of options, not a fait accompli. Robert Gates, the defence secretary, expressed continuing confidence in General McChrystal, but added that everyone involved in the review of strategy should provide their advice “candidly but privately”.

Mr Obama acted this week to fend off Republican claims that fear of his own wavering allies on Capitol Hill is weakening his commitment to a fight that he has always called vital to America’s security, both during the election campaign and since assuming office. On October 6th he invited 30 congressional leaders from both parties to the White House and told them that although he had not decided whether to send extra troops he was contemplating no “dramatic” reduction. The next day his security team convened again to continue their review, focusing this time on conditions in Pakistan. A final decision, says Harry Reid, the Senate’s majority leader, would probably come in “weeks, not months”.

Whether the right description of this timetable is “leisurely” (Senator John McCain) or “thorough” (the administration), the process has certainly been messy. The spat with General McChrystal, Mr Obama’s own recent choice to command in Afghanistan, invites the charge that he is not giving his generals the resources they need. If he does not send the general his extra troops, senior Republicans who have so far restrained their criticism will charge that the president is appeasing his party by endangering America’s fighting men overseas. Mr McCain has already called on Mr Obama to give “great weight” to his commanders’ views. But wading deeper into a war that this week entered its ninth miserable year will stoke the fears of the Democratic leadership in Congress that Mr Obama is sinking into a new Vietnam.

It is a fateful choice, and history is likelier to remember the decision itself, not the circumstances in which it was made. But Mr Obama’s failure to keep General McChrystal in line has made the politics of it very much harder. From Kandahar and Copenhagen (where Mr Obama faces a second ordeal in December at the climate-change summit) a cold wind is blowing through the White House.

Chicago's Olympic bid

The limits of

razzle-dazzle

The mayor mourns

|

|

|

|

| The sadness of Richard II |

RICHARD DALEY’S city was, until recently, one big Olympics advertisement. Olympians’ voices were piped through Chicago’s bus speakers. Olympic banners were draped across downtown bridges. Of all the people who supported Chicago’s bid to stage the 2016 games—from businessmen to the builders’ union to Oprah Winfrey—no one was more committed than the mayor. The Olympics would provide jobs, development and the international attention Chicago has desperately craved. For Mr Daley, Chicago’s boss since 1989, the Olympics would be his crowning triumph. Then, on October 2nd, Chicago lost.

Most politicians who pursue the Olympics, particularly those in developed countries, are doomed by definition. If they win the games, debt and scandal are likely. If they lose, humiliation is certain. Yet year after year leaders strap themselves to the stake and wait for the Olympic torch to light the pyre beneath them.

If all had gone as planned, the Olympics would have put the cap on a remarkable reign. Other Midwestern cities continue their post-industrial decline. Under Mr Daley’s watch Chicago has transformed for the better, with 3m residents and 29 Fortune 500 companies. Tourism has grown, thanks to lovely new and old parks, architecture and museums—plus a vast sparkling lake. The Chicago machine has evolved and improved from the corrupt days of Richard J. Daley, the mayor’s father. Richard II enjoys the support not just of developers and contractors but influential global firms. The Olympics—with its stress on private partnerships, tourism and global recognition—would have been the culmination of all this.

Instead, Copenhagen was the culmination of the worst year of Mr Daley’s tenure. The local economy, like that of so many other cities, has floundered. Chicagoans erupted over a botched scheme to privatise parking meters. Mr Daley faced more criticism in June when he said that Chicago would cover any Olympics cost overruns with its own cash. By late August only 47% supported the bid, according to a poll by the Chicago Tribune. By September Mr Daley’s approval rating had slipped to just 35%.

Now he faces an awkward reality. The games’ promises of quick jobs, development and transport investment have disappeared. A trend of nasty violence may well continue—on September 24th a teenager was beaten to death on the South Side. The city needs to close a budget gap of $520m. And the mayor must decide whether to run for re-election in 2011, when he will be 68. Winning the games would have tried Mr Daley’s mettle. A greater test will be how he recovers from losing them.

The economy's stumble

Air pocket or

second dip?

A slump in September

prompts thoughts of new stimulus

|

|

|

|

|

AFTER riding a wave of improvement since the spring, the economy stumbled in September according to the latest figures. Non-farm employment sank by 263,000, which was 62,000 more than in August, and the unemployment rate rose by 0.1% to 9.8%. Car sales tumbled as the federal “cash-for-clunkers” programme expired. Manufacturing activity cooled a bit.

All this is probably an air pocket; overall economic output almost certainly began to rise in the third quarter of the year and employment will eventually follow. Leading indicators such as the stockmarket and new claims for unemployment benefits are signalling recovery. But it is taking a painfully long time. “We will need to grind out this recovery step by step,” acknowledged Barack Obama on October 3rd, the day after the job data were released. To add insult to injury, the Bureau of Labour Statistics concluded that the economy lost 824,000 more jobs in the year to March than it had originally thought. That would raise the recession’s toll so far to 8m, or 5.8% of the workforce. Assuming no further revisions, the recession now holds the honour of the most severe since the second world war—exceeding even the 5% loss recorded in 1948.

The bigger problem is that once employment growth resumes, it will probably remain anaemic. More than half of businesses say they will not return to pre-recession staffing levels until 2012, if ever, according to a September survey of chief financial officers by Duke University and CFO Magazine, a sister publication of The Economist. Fully 43% still plan to cull payrolls in the next 12 months.

Mr Obama and his advisers are considering new measures to boost the economy. These will not be on the scale of this year’s $787 billion stimulus programme, which will in any case continue to inject money into the economy until the end of next year. More likely, he will seek to continue some provisions of the stimulus bill, such as extending unemployment benefits for laid-off workers and subsidies to allow them to keep their health insurance.

The retreat in car sales when cash-for-clunkers ended was a jarring reminder of the withdrawal symptoms that await when other stimulus measures, such as the homebuyer’s credit, are allowed to expire. But extending them would boost a soaring deficit that is estimated to have hit $1.4 billion in the fiscal year that ended on September 30th. Voters are nervous about red ink stretching away into the future, and even Mr Obama’s liberal supporters are turning up the heat. This week Nancy Pelosi, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, said a value-added tax should be “on the table”. It may yet come to that, though introducing such a tax too early would risk choking off the recovery and creating a brand new tax that would give the president’s enemies a field-day. No one said his job was easy.

The California governor's race

Early and heated

With eight months

until its primaries, California is drawing the stars

“THIS is a proud day for me,” beamed Gavin Newsom, the youthful mayor of San Francisco, as he stood among the bookshelves of a college in Los Angeles beside Bill Clinton, who had just endorsed him in his race to become governor of California next year. Former presidents don’t usually intervene in state primaries with eight months to go. But this is California, and the personalities and stakes are large.

On the Democratic side, Mr Newsom, known nationally mainly for his bold—though many say irresponsible—decision during the 2004 presidential campaign to recognise gay marriages in San Francisco, is running a distant second to California’s grand old man of politics, Jerry Brown. A former governor as well as the son of one, famous for his austerity in office and currently the attorney-general, Mr Brown has only just filed the paperwork to make his candidacy semi-formal. But in “matchup” polls Mr Brown is already ahead not only of Mr Newsom but of each of the three known Republican candidates. Mr Newsom trails behind all three.

Of these Republicans, the only one with the intellect and experience of government to match Mr Brown’s is Tom Campbell. Mr Campbell got his economics doctorate from the University of Chicago when Milton Friedman was his faculty adviser. Since then, he has spent 17 years in government—in the state senate, as a congressman, in the Reagan administration and as finance director of California—and 15 years at Stanford, Berkeley and Chapman University in southern California, where he now teaches.

If Mr Campbell is not the obvious Republican front-runner, this is mainly because he has much less money than his two billionaire challengers from Silicon Valley, Meg Whitman and Stephen Poizner. Ms Whitman is best known as the former boss of eBay, where she had a mixed record but a high profile. She has so far run almost entirely on business-school platitudes to avoid exposing herself to attack by the Republican right.

Mr Poizner, having made his money by founding and selling technology companies, is California’s insurance commissioner. A black belt in karate, he has been attacking Ms Whitman relentlessly, in part because this is so easy—it has emerged, for example, that Ms Whitman did not vote for much of her adult life and only became certifiably Republican suspiciously recently. But this strategy risks making Mr Poizner appear negative, especially if the polite and more issues-focused Mr Campbell is actually the one to beat.

The race is receiving a lot of early attention because California, the world’s eighth-largest economy and America’s biggest, remains in a dire condition. After several painful budget patches, it is likely to fall into the red again within months, or so reckons Mr Campbell. California already has the worst credit rating among the 50 states, and budget cuts have torn a hole in the state’s social safety-net.

The other reason comes down to its personalities. Mr Brown last became governor when he succeeded Ronald Reagan, who had in turn succeeded Mr Brown’s father. Now 71, he would be California’s oldest governor ever if re-elected. His colourful history includes a bitter enmity with Mr Clinton that dates from a clash during the 1992 presidential primary. This made it easy for Mr Brown to shrug off Mr Clinton’s endorsement of Mr Newsom this week. As though to counter Mr Clinton’s star power, Mr Brown has let it be known that Hollywood producers such as Steven Spielberg, David Geffen and Jeffrey Katzenberg are raising money for him rather than Mr Clinton’s man.

Gourmandising in Texas

Come fry with me

A new way to serve a

ball of butter

|

|

|

|

| You know you want to |

ON A fine afternoon at the Texas State Fair, a ringmaster encouraged a gaggle of children to flap their arms like butterfly wings. “What could possibly go wrong on a day as beautiful as today?” he asked. But a hundred yards away, something had gone quite wrong. People were queuing for an unusual delicacy: balls of butter, dipped in dough and cooked in a vat of boiling oil. Fried butter, in other words. The balls were dusted with a thin coat of powdered sugar. When bitten, they collapsed with an unctuous squelch.

Fairs are known for their decadent snack offerings. Most are unhealthy, and some push the conceptual boundaries of food into new territory. The Los Angeles County Fair, which ended on October 4th, featured a Meat Lovers’ Ice Cream Cone (don’t ask). The Minnesota State Fair is known for its foods-on-a-stick. The Texas fair bills itself as the fried food capital of the state.

The claim is credible. Sprinkled between the pig races and carnival rides are vendors selling fried ribs, fried guacamole, fried ice cream and even fried bacon. Fried butter is a new development. At the beginning of the fair it won an award for creativity. The inventor, Abel Gonzales, won the same award in 2006 for a different recipe—fried Coke.

Nutritionists would shudder at all the fat, sodium and trans-fats. Defenders say that the key is moderation. “If this is not your lifestyle, then it’s OK to indulge once or twice a year,” says a spokeswoman for the fair.

Opinions among fairgoers were divided. A woman selling toffee said that people had no business frying butter, with diabetes and high cholesterol as common as they are. She said she preferred to cook with olive oil. But a man eating a basket of fried butter with cherry jam was not too bothered. “It’s just butter,” he maintained.

Defending Manhattan

Extending the ring

of steel

New York expands its

counterterrorism monitoring system

|

|

|

|

| Here’s looking at you |

BARACK OBAMA visited the National Counter-terrorism Centre in Virginia on October 6th to heap thanks on the organisation for frustrating al-Qaeda’s tricks. He praised the co-ordination between federal, state and local partners, in particular pointing out that members of New York’s police department (NYPD) now play a crucial role. He pledged to keep America safe and to “give all of you the tools and support you need to get the job done, around the world and here at home”. About time too, New Yorkers reckon. The city spent $300m of its own money last year on counter-terrorism, according to Ray Kelly, New York’s police commissioner.

Michael Bloomberg, the mayor, and Mr Kelly announced on October 4th that a new grant of $24m from the Department of Homeland Security will be used to expand the Lower Manhattan Security Initiative so that it can take in midtown Manhattan as well. The initiative, which dates back to 2005, involves an extensive network of security cameras, licence-plate readers and weapon-detectors which work together to spot threats and deter terrorist surveillance. Several thousand cameras, many provided by private companies, will now cover transport hubs like Grand Central Station, Penn Station and Times Square.

Bruce Schneier, a security guru, calls this “cover-your-ass security”, not unlike taking off shoes at airports. He worries that the ring of steel will not deter attackers, but merely force them to change targets. It is far better, he says, to invest in security that defends against a broad spectrum of attacks, namely “intelligence, investigation and emergency response”. These three tactics led to the arrest of Najibullah Zazi, an Afghan immigrant, who pleaded not guilty last month to conspiracy to use weapons of mass destruction in New York.

“Hiring Arabic translators doesn’t get you votes,” says a cynical Mr Schneier. But to be fair to the NYPD, recruits who are native speakers of languages such as Arabic, Pushtu and Bengali are often assigned to counter-terrorism duties. Mr Kelly starts every morning with a counter-terrorism briefing. His force has assigned 1,000 of its officers to the task of fighting terrorism and sends officers from the outer boroughs to patrol potential midtown targets, such as buildings belonging to financial firms. The struggle goes on.

Teenage pregnancies

Growing pains

After a long, steady

fall, a troubling rise

|

|

|

|

|

SOME blame demography, others the recession. It might have something to with gender roles, or the steady stream of mixed messages about being a teenage mum. Perhaps sexually transmitted infections are not the deterrent they once were. Or maybe everyone is suffering from a touch of “prevention fatigue”.

On one point, however, experts agree: when it comes to teenage births, the United States is backsliding. Between 1991 and 2005 the teenage birth rate declined by 34%, according to the National Centre for Health Statistics. Between 2005 and 2007, the last year for which statistics are available, it crept up 5%.

Teenage births are nothing new and in 1960, pre-Pill, the rate in America was more than double what it is today. It is still well below its early-1990s bubble, but experts are getting worried about the trend line.

Consider Texas. The state requires only that public schools emphasise abstinence, not that they forsake all other approaches. Any district could choose to be more comprehensive. But few do. Last year the Texas Freedom Network, a religious-freedom watchdog, gathered curricular materials from the state’s public-school districts. Their findings, published earlier this year, are disturbing. Fully 94% of the districts took the abstinence-only approach. Those pamphlets and brochures that bothered to discuss contraceptives were often full of errors, or deliberately misleading.

The materials also traded on shame and fear. Across the state teenagers were warned that premarital sex could lead to divorce, suicide, poverty and a disappointed God. One district staged a skit about a young couple on their honeymoon. The husband presented his bride with a beautiful wrapped present that he had been saving for years. Her gift for him was in tatters.

This approach does not seem to be working. Texas has the third-highest rate of teenage births, after Mississippi and New Mexico. Dallas has the highest rate of repeat teenage births in the country, 28%, according to a September report from Child Trends, and several other Texas cities are in the top ten. In a nice illustration of Texan conservatism, girls under 18 have to get parental consent for prescription contraceptives, even if they already have a child.

Abstinence-only education makes a convenient scapegoat. But attacking it is a bit of a distraction. Many states and school districts have already abandoned it in favour of a more comprehensive approach. More will, since federal funding for one abstinence-only programme was ended in June. Barack Obama apparently does not want to renew abstinence-only funding, though last month the Senate Finance Committee, hashing out its health-care bill, approved an amendment restoring such funds.

Abstinence aside, experts suggest a more holistic approach. Latina teenagers, for example, have a considerably higher birth rate than any other group, even though they have similar rates of sexual activity. Silvia Henriquez, the executive director of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Health, reckons that access is the problem. Latina teenagers are less likely to have health-care coverage for contraceptives, and are more likely to lack transport to the free clinics in their cities.

Youngstown, Ohio

A young town again

A blighted city may be

(slowly) recovering

|

|

|

|

| Time to start over |

THE battle for America’s future, so Barack Obama said earlier this year, “will be fought and won in places like Elkhart and Detroit, Goshen and Pittsburgh, South Bend [and] Youngstown”. Or maybe fought and lost; Forbes.com had just called Youngstown, in Ohio, one of the ten fastest dying cities in the country.

The corrosion of the Midwest is an often-told tale. Cities like Youngstown remained too reliant on one sector, manufacturing, well into the 1970s. When that sector collapsed, so did the city. By the time the lessons of diversification had been learned, the population in Youngstown had fallen by half. Home to 170,000 in the 1950s, it now holds just 75,000 people.

Youngstown’s problems have been manifold. The exodus of steel that began in 1977 left, by some accounts, 50,000 unemployed in its wake. To make matters worse, the city was in the grip of organised crime. A mafia-run contractor was famously once hired to resurface a street with two-inch deep asphalt for $2m. They laid one inch, and pocketed the extra $1m.

But now there are a few signs that things are starting to improve. One example is the Youngstown Business Incubator, which provides cheap office space and other assistance to start-ups that specialise in business software. Founded using government seed money 14 years ago in a part of downtown where few dared to venture, let alone start a business, it is now thriving. Its star pupil, with nearly 200 employees, is Turning Technologies, which has outgrown its original space and been forced to move to a separate building nearby. Jim Cossler, head of the Incubator, expects more growth as more start-ups join Turning Technologies and the 13 others currently there. He says he has convinced a software company from San Francisco to send some employees to Youngstown, not least because—according to him—the rent is 4% of what it would be in San Francisco.

|

|

|

|

|

Youngstown was designed for lots of people but is occupied by just a few. Art museums and theatres are surprisingly abundant for a population its size, and the city sprawls. But the tax base can no longer support such grandeur. So Jay Williams, the mayor, wants to shrink the city. He plans to use federal stimulus funds to demolish areas with high vacancy rates and turn them into green space for parks or even farms. Displaced families will be helped to move to new neighbourhoods.

At the moment it is unclear what others can learn from all this. The plan may not even be working. Unemployment, now 13.2% in the region, has risen against the national average. Yet for the first time in years morale in the city seems to have improved. One developer is hard at work converting old downtown high-rises into stylish new apartments. And Federal Plaza, the once abandoned main drag, is now speckled with a few clubs and restaurants. On Friday and Saturday nights, twenty-somethings spill out onto the pavements. Now all Youngstown has to do is keep them.

Lexington

Of debt and

deadbeats

A new culture war is

brewing over capitalism

|

|

|

SEVENTEEN Uncle Sams were seen begging on the streets of Washington, DC, this week. They were a sad sight, with their slightly bedraggled red, white and blue hats and their cardboard signs with the hand-scrawled plea: “I want YOU to give me $12 trillion.” It was a publicity stunt, of course, staged by DefeatTheDebt.com, a fiscally hawkish pressure group. But it captured something important about the national mood.

Unemployment is nearly in double digits. Most Americans think the economy will recover next year, but only 2% think it will make a complete recovery. And many are worried about Uncle Sam’s ongoing borrowing binge. Has all that money averted disaster and eased the pain of the recession, as Barack Obama insists? Or did it merely postpone the pain? DefeatTheDebt.com’s television commercials leave no room for doubt. A classroom full of children stand as if to recite the pledge of allegiance, but the words are different: “I pledge allegiance to America’s debt, and to the Chinese government that lends us money, and to the interest, for which we pay, compoundable, with higher taxes and lower pay, until the day we die.”

Many Americans think much of this money might as well have been tied up in bundles and burned. On average, according to Gallup, Americans believe that 50 cents of every dollar the federal government spends is wasted. This is an outlandish figure. Not even the Department of Agriculture is that profligate. Yet even Democrats, who are supposed to believe in big government, guess that 41 cents of every federal dollar is wasted. Republicans think it is 54 cents, and independents, whose votes Democrats will sorely need at the mid-terms next year, are if anything slightly more cynical, putting the number at 55 cents in the dollar.

The hyperkinetic Mr Obama is trying to fix everything from car firms and banks to Chicago’s Olympic bid. Yet a poll last month found that most Americans would rather their government did less. Some 57% said it was doing too many things that were better left to individuals and businesses. Only 38% thought it should do more. The proportion who believe that government over-regulates private businesses has also risen from 38% to 45% in a year. And despite the attention lavished on Michael Moore’s new movie excoriating capitalism, only 24% of Americans think firms are under-regulated.

Arthur Brooks, the head of the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think-tank, feels that the real culture war in America today is not about gay marriage or abortion, divisive though those issues are, but about capitalism. Everyone agrees that Wall Street messed up last year, but many are disturbed by the expansion of government that followed the crash. Voters particularly dislike the way the state is using their money to reward deadbeats, says Mr Brooks. They themselves work hard and live within their means. They see their neighbour, who borrowed more than he could afford to buy a fancy house, getting a bail-out to save him from the consequences of his own poor judgment. They see reckless bankers getting bailed out too, and the ill-managed carmakers of Detroit likewise. And they resent it.

There is some truth in Mr Brooks’s analysis. The bank and car bail-outs were indeed unpopular. And the fear that the Democrats aim to make government too big, too expensive and too intrusive set off a wave of “tea-party” protests that is still rolling. Democrats have tried to dismiss the tea parties as motivated by racism, because Mr Obama is black. But racism cannot explain why the president’s approval rating has fallen this year. As Mr Obama observed: “I was actually black before the election.”

Some of the critics of big government are a bit hysterical. Glenn Beck, a talk-show host, foments panic and then urges listeners to buy gold from a company he endorses. Michelle Malkin, a blogger, has written a bestselling book about the Obama administration called “Culture of Corruption”. This is silly, but the rabble-rousers are popular because their audience has genuine grievances. Many working-class men have lost their jobs. Those who are still employed have seen their wages stagnate and their pensions shrivel in the stockmarket crash. Their health insurance is insecure, but they don’t trust Congress not to make it worse.

Meanwhile, they can see that one group of Americans has been practically unaffected by the recession: government employees. Their hours have not been cut, their benefits are gold-plated and they are almost impossible to sack. In good times, few Americans notice these things, but in bad times, the disparity grates. Cops and firefighters can retire in their 40s and draw defined-benefit pensions for life. With overtime, one tenth of the police in Massachusetts made more than the governor’s annual salary in 2006, according to the Boston Globe. Including benefits, the average employee of New York City makes more than $100,000, according to Forbes, while some Californian prison guards “sock away $300,000 a year”.

And what do taxpayers get for their generosity? The bad bargains get all the publicity. Union contracts force the postal service to pay thousands of unneeded workers to do nothing. In New York, public-school teachers who can’t be trusted to teach but can’t be sacked either are paid to sit and do crosswords.

One should not overstate the rage of taxpayers against public servants. Most Americans admire firemen, teachers and cops. They like receiving government benefits, too. And roughly half of them will pay no federal income tax at all this year. The problem is that this is not sustainable. During his election campaign, Mr Obama promised not to raise taxes on anyone except the rich, but with the deficit so vast, the question is not whether he will break this promise but when.

![]()